By Grace Reamer

As the Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery celebrates its 30th anniversary, we are taking a look back at the people and the activities that brought about the formation and development of this unique organization and partnership.

For Phil Hamilton of the Muckleshoot Tribe, salmon fishing is a birthright. He remembers when his grandmother was the tribal chair during the “fish wars” of the early 1970s, until the federal court Boldt Decision affirmed tribal rights to half of the harvestable salmon. He remembers how his father worked on the legal issues surrounding fishing rights guaranteed by 100-year-old treaties.

Today, after 43 years working with the Muckleshoot Tribe, Phil serves as a member of the tribal Fisheries Commission, overseeing management of the Fisheries Department. That includes raising salmon at tribal hatcheries as well as supporting the state-owned Issaquah Salmon Hatchery. The chinook and coho raised in Issaquah populate the Greater Lake Washington Watershed and historic fishing grounds for the Muckleshoot Tribe.

His reverence for salmon goes further than fishing. Hamilton also expresses his heritage and talent in traditional tribal artwork through painting and embroidery, often focusing on images of the iconic Northwest salmon. That’s why it was natural that Steve Bell, the first director of the Friends of the Issaquah Salmon Hatchery, would contact Hamilton more than 20 years ago about including a native art installation in the hatchery rebuilding project. Bell asked him if he could share any traditional salmon origin stories, and Hamilton suggested just the thing.

The Muckleshoot story of The Salmon People and Raven “has been handed down over many years,” Hamilton said. “It shares how, in the past, tribes recognized how salmon are having a difficult time surviving.” The story of how the trickster Raven and his sidekick Mouse visited the Salmon People and brought back salmon to their village includes the ritual of returning the bones of the first fish back to the river to ensure renewal of the species.

That ritual demonstrates the natural cycle of spawning salmon that contribute the nutrients they brought from the ocean to nourish the entire ecosystem around the rivers. It also serves as a metaphor for the need to supplement fish populations to support humans as well as the natural environment, Hamilton noted. That made it a perfect story to illustrate the importance of hatchery operations as well as the cultural connection between salmon and the Northwest’s first people.

Hamilton illustrated the story with line drawings and intricate designs of salmon, the raven, canoes and the people of the salmon village. Those drawing were then etching in seven granite boulders, along with the text from the story, and installed in a semicircle on the hatchery grounds in 2002, as part of the third and final phase of redevelopment. A grant from the Issaquah Arts Commission funded the installation. Today, it is a tranquil corner when some come to make rubbings of the etched art, others stop to read the story aloud, and children climb and play on the boulders.

The sculpture also recognizes the role of the Muckleshoot Tribe as co-managers of the local salmon runs, along with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. In addition to managing the fish counts at the Ballard Locks, the Tribe also reviews permits for development and logging to make sure they are protecting salmon habitat, and advocates replacement of fish-blocking culverts under roads to open up stream habitat that has been blocked.

The last few Fridays of the season brought Muckleshoot employees out dressed in their best Seahawks gear for a group photo to show that the 12’s spirit runs deep.

The two core components of the 7th annual Salmon Jam tournament are teaching kids the dangers of smoking cigarettes and vaping, and empathy for others.

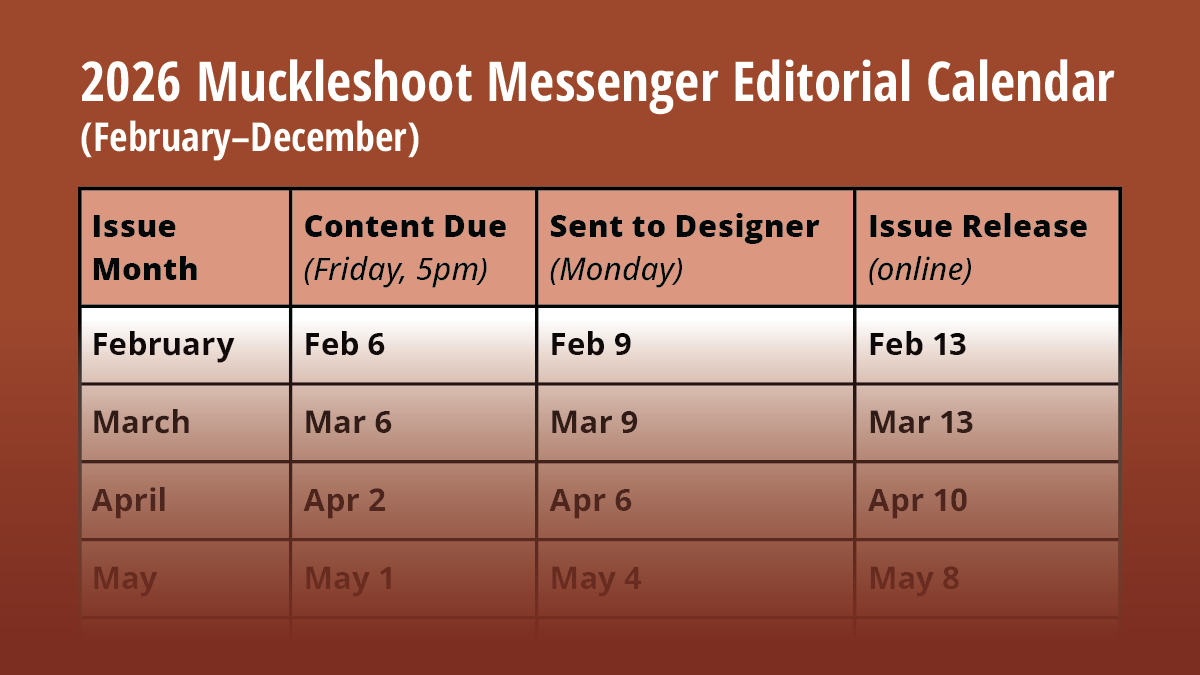

We love hearing from our community. To help us share stories in a timely and organized way, all content for the Muckleshoot Messenger is due by 5pm on the first Friday of each month.

Elders from the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe and their loved ones gathered together on Jan 16 at the Elders complex to celebrate the New Year. The gathering was a joyful and welcoming community celebration.

The Muckleshoot Messenger is a monthly Tribal publication. Tribal community members and Tribal employees are welcome to submit items to the newspaper such as announcements, birth news, birthday shoutouts, community highlights, and more. We want to hear from you!